Election of a Pope 1

Death of the Pope

The Cardinal Camerlengo proclaims a papal death

The death of the pope is verified by the Cardinal Camerlengo, or Chamberlain, who traditionally performed the task by gently striking the pope’s head with a small silver hammer and calling out his Christian (not papal) name three times. During the twentieth century the use of the hammer in this ritual has been abandoned; under Universi Dominici gregis, theCamerlengo must merely declare the pope’s death in the presence of the Master of Papal Liturgical Celebrations, and of the Cleric Prelates, Secretary and Chancellor of the Apostolic Camera.

The Cardinal Camerlengo takes possession of the Ring of the Fisherman worn by the pope. The Fisherman’s Ring is a signet used until 1842 to seal official documents signed by the Pope. The ring, along with the papal seal, is later destroyed before the College of Cardinals. The tradition originated to avoid forgery of documents, but today merely is a symbol of the end of the pope’s reign.

During the sede vacante, as the papal vacancy is known, certain limited powers pass to the College of Cardinals, which is convoked by the Dean of the College of Cardinals. All cardinals are obliged to attend the General Congregation of Cardinals, except those whose health does not permit, or who are over eighty (but those cardinals may choose to attend if they please). The Particular Congregation, which deals with the day-to-day matters of the Church, includes the Cardinal Camerlengo and the three Cardinal Assistants—one Cardinal-Bishop, one Cardinal-Priest and one Cardinal-Deacon—chosen by lot. Every three days, new Cardinal Assistants are chosen by lot. The Cardinal Camerlengo and Cardinal Assistants are responsible, among other things, for maintaining the election’s secrecy.

The Congregations must make certain arrangements in respect of the pope’s burial, which by tradition takes place within four to six days of the pope’s death, leaving time for pilgrims to see the dead pontiff, and is to be followed by a nine-day period of mourning (this is known as thenovemdiales, Latin for “nine days”). The Congregations also fix the date and time of the commencement of the conclave. The conclave normally takes place fifteen days after the death of the pope, but the Congregations may extend the period to a maximum of twenty days in order to permit other cardinals to arrive in the Vatican City.

Resignation of a pope

A vacancy in the papal office may also result from a papal resignation. Until the resignation of Benedict XVI on 28 February 2013, no pope had abdicated since Gregory XII in 1415. In his book The Light of the World Benedict XVI had espoused the idea of abdication on health grounds which already had some theological respectability.

Papal Conclave Elects a Pope

A papal conclave is a meeting of the College of Cardinals convened to elect a new Bishop of Rome, also known as the Pope. The pope is considered by Roman Catholics to be the apostolic successor ofSaint Peter and earthly head of the Roman Catholic Church. The conclave has been the procedure for choosing the pope for more than half of the time the church has been in existence, and is the oldest ongoing method for choosing the leader of an institution.

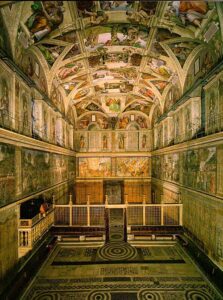

The 1492 conclave was the first to be held in the Sistine Chapel, the site of all conclaves since 1878.

A history of political interference in papal selection and consequently long vacancies between popes, culminating in the interregnum of 1268–1271, the longest election of a pope because of infighting between the cardinals.

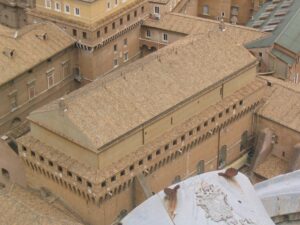

Pope Gregory X decreed during the Second Council of Lyons in 1274 that the cardinal electors should be locked in seclusion cum clave (Latin for “with a key”) and not permitted to leave until a new Bishop of Rome had been elected. Conclaves are now held in the Sistine Chapel of the Apostolic Palace.

Since the Apostolic Age, the Bishop of Rome, like other bishops, was chosen by the consensus of theclergy and laity of the diocese. The body of electors was more precisely defined when, in 1059, the College of Cardinals was designated the sole body of electors. Since then, other details of the process have developed. In 1970, Pope Paul VI limited the electors to cardinals under 80 years of age.

The current procedures were established by Pope John Paul II in his apostolic constitution Universi Dominici gregis as amended by motuproprios of Pope Benedict XVI dated 11 June 2007 and 25 February 2013. A two-thirds supermajority vote is required to elect the new pope, which also requires acceptance from the person elected.

The procedures relating to the election of the pope have undergone almost two millennia of development. Procedures similar to the present system were introduced in 1274 with the promulgation of Ubi periculum by Gregory X, based on the action of the magistrates of Viterbo during the interregnum of 1268–1271.

Conclaves

To resolve prolonged deadlocks in the earlier years of papal elections, local authorities often resorted to the forced seclusion of the cardinal electors, such as that first adopted by the city of Rome in 1241, and possibly before that by Perugia in 1216.[55] In 1269, when the forced seclusion of the cardinals alone failed to produce a pope, the city of Viterbo refused to send in any materials except bread and water. When even this failed to produce a result, the townspeople removed the roof of the Palazzo dei Papi in their attempt to speed up the election.[56]

In an attempt to avoid future lengthy elections, Gregory X introduced stringent rules with the promulgation of Ubi periculum. Cardinals were to be secluded in a closed area and not accorded individual rooms. No cardinal was allowed, unless ill, to be attended by more than two servants. Food was supplied through a window to avoid outside contact.[57] After three days of the conclave, the cardinals were to receive only one dish a day; after another five days, they were to receive just bread and water. During the conclave, no cardinal was to receive any ecclesiastical revenue.[12][58]

Gregory X’s strict regulations were abolished in 1276 by Adrian V, but Celestine V, elected in 1294 following a two-year vacancy, restored them. In 1562, Pius IV issued a papal bull that introduced regulations relating to the enclosure of the conclave and other procedures. Gregory XV issued two bulls that covered the most minute of details relating to the election; the first, in 1621, concerned electoral processes, while the other, in 1622, fixed the ceremonies to be observed. In 1904, Pope Pius X issued a constitution consolidating almost all the previous rules, making some changes. Several reforms were also instituted by John Paul II in 1996.[10]

The location of the conclaves was not fixed until the fourteenth century. Since the Western Schism, however, elections have always been held in Rome (except in 1800, when French troops occupying Rome forced the election to be held in Venice), and normally in what, since the Lateran Treaties of 1929, has become the independent Vatican City State. Since 1846, when the Quirinal Palace was used, the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican has always served as the location of the election. Popes have often fine-tuned the rules for the election of their successors: Pope Pius XII‘s Vacantis Apostolicae Sedis of 1945 governed the conclave of 1958, Pope John XXIII‘s Summi Pontificis Electio of 1962 that of 1963, Pope Paul VI‘s Romano Pontifici Eligendo of 1975 those of 1978, and John Paul II‘s Universi Dominici gregis of 1996 that of 2005.[59]

Modern practice

In 1996, John Paul II promulgated a new Apostolic Constitution, called Universi Dominici gregis, which with a slight modification by Pope Benedict XVI now governs the election of the pope, abolishing all previous constitutions on the matter, but preserving many procedures that date to much earlier times.

Under Universi Dominici gregis, the cardinals are to be lodged in a purpose-built edifice, the Domus Sanctae Marthae, but are to continue to vote in the Sistine Chapel.

Domus Sancta Martha

Domus Sancta Martha

Several duties are performed by the Dean of the College of Cardinals, who is always a Cardinal Bishop. If the Dean is not entitled to participate in the conclave owing to age, his place is taken by the Sub-Dean, who is also always a Cardinal Bishop. If the Sub-Dean also cannot participate, the senior Cardinal Bishop participating performs the functions.[61]

Since the College of Cardinals is a small body, there have been proposals that the electorate should be expanded. Proposed reforms include a plan to replace the College of Cardinals as the electoral body with the Synod of Bishops, which includes many more members. Under present procedure, however, the Synod may only meet when called by the pope. Universi Dominici gregis explicitly provides that even if a synod or an ecumenical council is in session at the time of a pope’s death, it may not perform the election. Upon the pope’s death, either body’s proceedings are suspended, to be resumed only upon the order of the new pope.[62]It is considered poor form to campaign for the position of pope. However, there is inevitably always much speculation about which Cardinals have serious prospects of being elected. Speculation tends to mount when a pope is ill or aged and shortlists of potential candidates appear in the media. A Cardinal who is considered to be a prospect for the papacy is described informally as a papabile (an adjective used substantively: the plural form ispapabili), a term coined by Italian-speaking Vatican watchers in the mid-twentieth century, literally meaning “pope-able”.